Theology that prays before it punches

An experiment in trying to think Catholic and be Catholic at the same time

If you are a theologian, you truly pray. If you truly pray, you are a theologian.

- Evagrius Ponticus

In 2015, I was burnt out. I had been blogging for five years at The Conciliar Anglican, and to my astonishment the audience had grown beyond anything I ever expected. Then one day, I realized that I had lost control of it.

When I created that blog, it was meant to be a place for me to explore ideas about what it means to be Anglican in a world of Christian plurality. I was trying to get my head to catch up with my heart. I had become an Episcopalian in my twenties, after walking away from my Catholic upbringing as a teenager. After years of struggling to find faith in isolation, Anglicanism had seemed like an oasis in the desert, but as I entered my thirties, something seemed to be missing. Unlike other Christian traditions, Anglicanism did not seem to have a raison d’etre. It was born out of historical accident as much as theological conviction. I had been ordained in the Episcopal Church for several years, but I could not tell you what it stood for. I found that I could not reconcile that with the calling of the Scriptures to be united in one Church under Christ as the head. If I was going to be an Anglican Christian, it had to mean something. It had to be more than just the “easiest pier to fish from,” as one of my Evangelical Anglican friends described it.

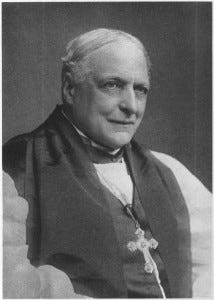

I called the blog The Conciliar Anglican because I was looking for the Church of the councils. Another friend described Anglicanism as the place where St. Thomas Aquinas and John Calvin could sit together in the same pew. I have a strong affinity for Eastern Christian spirituality, and so I wanted Vladimir Lossky and St. Mary of Egypt to join them in that pew. That quest brought me to Charles Chapman Grafton, a late nineteenth century American Anglican bishop who spent a lifetime trying to synthesize the kind of marriage between Anglo-Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy that I longed for. Reading Grafton led me to the Anglican high churchmen of the seventeenth century. It was there, for the first time, that I found what I believed to be an Anglicanism with a coherent theological vision, rooted in the Book of Common Prayer and the early Church Fathers, open to mystery and yet confident in its own purpose. I found this search to be exciting and gratifying, and I began to write about it regularly.

Yet something darker was happening to me in the midst of all of this. I discovered that when I would write a blog post that simply reflected on the joy of following Jesus or the fruit of prayer, it did not gain much attention. But when I posted something brash, something that made claims to certainty while also rhetorically punching someone else in the face, the number of views increased exponentially. And so, slowly, this became the kind of post I would write all the time.

My search for theological clarity led me to many celebrated Christian apologists of our day. I read their books, listened to their podcasts, and even corresponded with some of the great defenders of Catholicism, Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, and Calvinism. These folks were different from the ecumenical hodgepodge of Christian thinkers I had gotten to know in seminary. They had ideas that were intellectually stimulating, but they also had clever ways of using those ideas to destroy their opponents. They could cut you to ribbons with a single phrase, and they were absolutely convinced of their own rightness. Many of them used new media forms like YouTube and internet radio to get their ideas across. They were cool, and I wanted to be cool too. So I started adopting their methods, attacking the same kind of straw men that they did, making my own YouTube videos to go along with the blog posts, and my audience grew ten-fold. Suddenly, I was receiving emails from people all over the world who thought I had the answers. I got invited to speak at conferences and to join the boards of various organizations. Meanwhile, my content was becoming more narrow, more combative, and less and less prayerful.

Apologetics has always been a rough business. Many of the seventeenth century Anglican writers I celebrated wrote with barbed tongues about their interlocutors. In so doing, they were following in the footsteps of the early Church Fathers who were certainly not strangers to the art of the well-placed insult. It is easy to understand why apologetics can become so heated. After all, Christian apologetics is the art of giving a reasoned defense for the faith. One generally does not need to defend what is not under attack. But the Christian apologists of bygone eras were fighting in a different arena. They could assume a basic level of rhetorical savvy on the part of their audience that has been erased in our day and age by the almighty “hot take.”

Even in the first half of the last century, when there was already widespread and growing ignorance about basic tenets of the Christian faith, it was still reasonable to expect that an intelligent person could sit still long enough to contemplate an idea. G.K. Chesterton and C.S. Lewis could both throw a mean punch, but it generally came at the end of a carefully thought-out argument. Nowadays, thanks to the advent of social media, no statement is allowed to be made in context, and so every tweet or post is a full-blown sock in the jaw. Apologetics has become divorced from authentic theology. The Fathers could get away with being saucy occasionally because they spent the majority of their time on their knees, worshipping God in the beauty of holiness. The contemporary apologist can spend every waking moment defending God’s honor without ever having to spend any time with God at all.

Not only did this kind of thinking disrupt my search for truth, it also gave me a distorted picture of what truth would look like were I ever to find it. By necessity, apologetics tends to be heavy on doctrine, but contemporary apologetics pushes that to an absurd extreme. All truth becomes propositional. Therefore, the only way I could ever embrace one of the traditions defended by the apologists would be to come to a place of complete intellectual assent. I could never become Catholic, or Orthodox, or Lutheran, or anything else unless and until I was ready to say, unequivocally and unambiguously, that everything my newfound tradition proposed was absolute truth and everything that came from other places was, at best, merely a lesser version. It was all about me and what was happening in my head, not about God. There would be no room for emotions in my discernment, let alone for leadings of the Holy Spirit. There is a surprising amount of Stoicism mixed in with contemporary apologetics.

All of this made me feel trapped by the house of cards I had built. It was not that the Anglicanism I was proposing was incoherent or inchoate, but it was unable to bear the weight I was trying to place upon it. And that was my fault, not the fault of any of the dear readers who responded so movingly to my words, nor the fault of my beloved seventeenth century divines. I allowed the medium not only to become the message but to drive it. God became a math problem that I knew how to work, rather than the living, beating heart of being itself.

Then one day, while I was pacing alone in the dark sanctuary of the church I pastored, the math problem decided to leap off the page and speak to me. And it said, “I want you to become Catholic.”

This made zero sense to me. Of all the available options, it was one of the lowest on my list. I had good, rational, reasonable answers to the Catholic apologists. I did not find their arguments at all satisfying. I knew that becoming Catholic meant a major disruption to my life and to my family. At the time, I did not feel particularly convicted that the Catholic Church was in any sense more true than the one I happened to be standing in. There was, in other words, no good reason at all to follow this direction, except one: it had come from God. He had met me in prayer and told me where He wanted me to go and what He wanted me to do.

It took me almost two years from that day to unlearn enough of my bad habits that I could finally say yes to the Lord’s leading. The day I became Catholic again was both the happiest and saddest of my life. I remember saying out loud with great joy, over and over, “I am a Roman Catholic.” And then the joy faded as I followed that by saying, also over and over, “I am not a priest.” But since then, the Lord has seen fit to bring me into the Catholic priesthood, and I can say today, with joy and astonishment, that the Catholic Church is where all that is good, true, and beautiful converge to reveal the heart of Jesus Christ to the world. Along the way, I have learned how to see the truth of the Church’s teaching as a plowshare rather than a sword.

Perhaps I am merely projecting my own desires, but I believe there is a hunger today for a different kind of apologetics, especially among committed Catholics who find repugnant both the searing politics of so-called traditionalism and the mindless sentiment of liberalism. There has to be a way of exploring, experiencing, and even fighting for the great truths of the Catholic faith without having to bloody the nose of the person two pews over in the process. Theology can be intellectually rigorous, but it is not first and foremost an academic discipline. Before it is anything else, it is a form of prayer. If that is not where apologetics both begins and ends, it is utterly useless. A truly Catholic apologetics will invite the kind of deep engagement with the mystery of God that makes the hair on the back of your arms stand on end. It will be faithful to the magisterium of the Church without descending into a proxy battle over politics. It will be fed by the liturgy without becoming another decoy for the culture wars. It will be as concerned with knowing God as it is with knowing about Him. It will be ecumenical in the best sense of the word, neither glossing over Catholic distinctiveness nor glibly dismissing the graces God has imbued into the traditions of other Christians (See Ut Unum Sint for more information).

Can I provide that kind of apologetics? I have no idea, but I would like to try to contribute something to it, and I hope others will join me. I doubt the algorithm overlords who control what we see and what we do not will take kindly to this project since it will not be built on a platform of anger-fueled consumption. Nevertheless, I would rather talk to a small group about God than a large group about my own insecurity. God does not fit neatly into sound bytes or tweets, but the more we turn our attention away from ourselves and towards Him, the more even our sound bytes and tweets can be transformed into instruments of faith, hope, and love.

I very much loved this piece, particularly this:

"Perhaps I am merely projecting my own desires, but I believe there is a hunger today for a different kind of apologetics, especially among committed Catholics who find repugnant both the searing politics of so-called traditionalism and the mindless sentiment of liberalism."

I feel seen and heard. And there are a lot of folks out there who whisper these same sorts of things to me. Tired of the deep divides, the senseless noise, the mean dichotomies.

Thanks, and I'll be reading along.

Good gravy. Thank you for writing this out.